Book ExcerptJust American

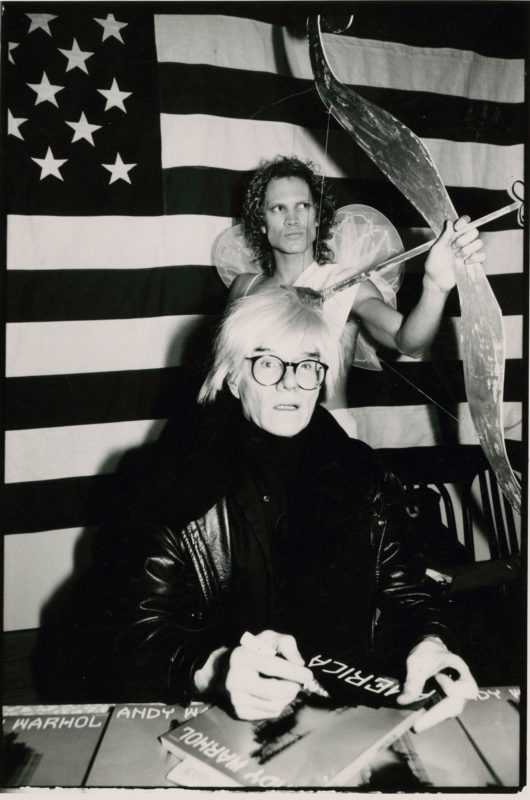

Sebastian Piraz, Andy Warhol at a book signing for America, 1985. Photo credit: Sebastian Piraz/Redux

Image Gallery

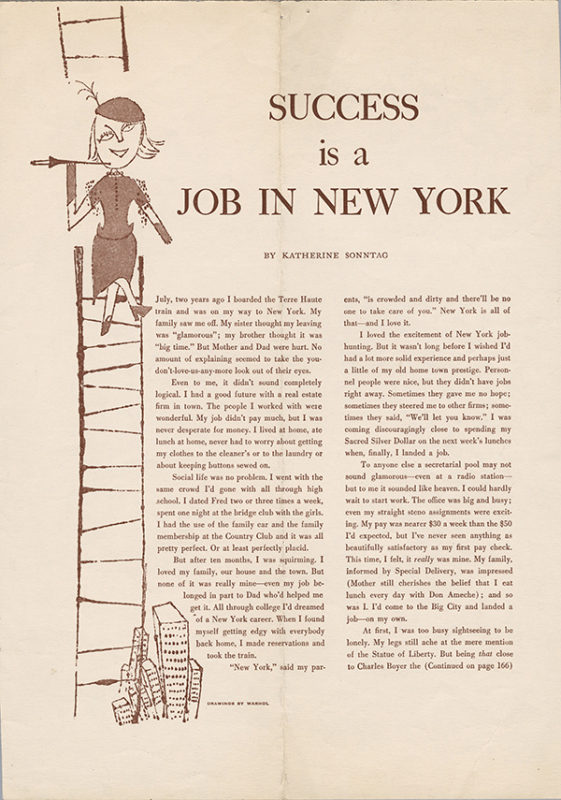

Warhol’s first assignment as a professional artist in New York consisted of illustrations for a group of articles in Glamour magazine published under the heading “What Is Success?” The articles, by various writers, provided different answers to the question, and one of them was titled “Success Is a Job in New York.” The text was written by a young woman who had abandoned a “perfectly placid” life and took a train to the Big Apple with big aspirations and a thirst for adventure.2 Her story aligned with that of Warhol, who, upon leaving Pittsburgh, dropped the final a in his surname and was on the way to becoming a leading commercial illustrator.

Like Warhol or the journalist who defined her idea of success in the pages of Glamour, the contemporary artists represented in Fantasy America, some native New Yorkers and others transplants, have all pursued careers in the city. These artists—Nona Faustine, Kambui Olujimi, Pacifico Silano, Naama Tsabar, and Chloe Wise—address contemporary culture in the United States three decades after Warhol. All are, like Warhol, multidisciplinary artists who produce work that blurs the boundaries between form and concept, offering a complex picture of contemporary life. Faustine confronts modern injustices through photographs centered on public monuments and buildings related to hidden African American histories. Olujimi addresses nationhood and the colonization of bodies, land, time, and space, surfacing buried political pasts. Silano rearranges tear sheets from vintage gay magazines to explore love and loss in queer culture. Tsabar uses her body and sound compositions to perform outside the boundaries of gender norms with an array of female and gender-nonconforming collaborators. Wise deconstructs advertising and audience through staged narratives in painting and film to reveal tenuously manufactured social contracts and constructs. All are, in different ways, reflecting on their own custom-made “dream Americas” while providing incisive commentary on the real one that we all live in.

* * *

In the 1950s Warhol achieved success as an adman, becoming one of the industry’s most in-demand commercial artists. By 1961, however, he would develop a new artistic style and establish himself as a Pop artist occupying the center of attention among his contemporaries and patrons. As Pop art spread across the country, Warhol began silk-screening portraits of Jackie Kennedy, Brillo Box sculptures, and the 13 Most Wanted Men, a mural commission for the 1964 New York World’s Fair that was censored because of the (desirable) criminals depicted. That year Warhol went to Paris, where he had his first European solo show and debuted the Death and Disaster paintings, which featured gory images taken from mass media. His original working title for the show, Death in America, went unused, but the artworks were understood immediately.3

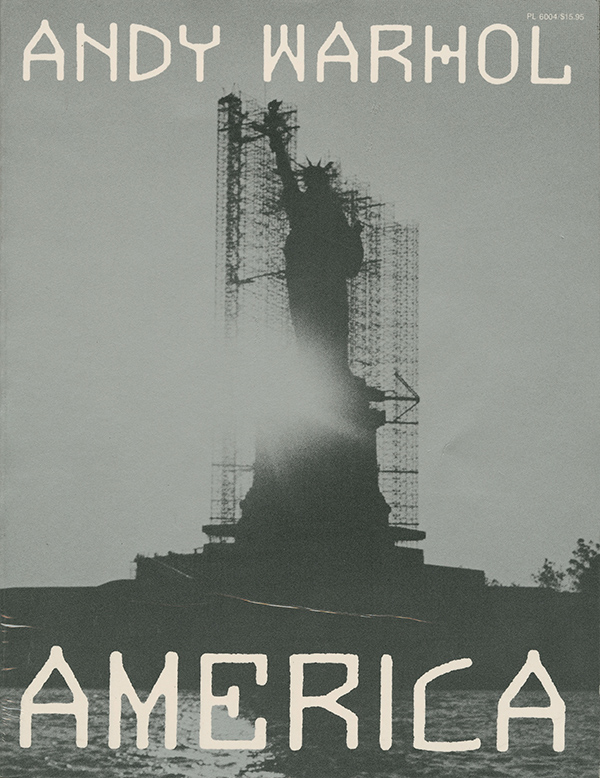

By the 1980s Warhol was one of the most recognized living artists and cultural icons. His hopscotching around creative disciplines allowed him to make films, publish Interview magazine, receive lucrative commissions, pursue a late modeling career, and produce Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes for the newly launched music channel MTV. Warhol also created many books during his lifetime. Early in his career he illustrated self-published books, including 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy (1954) and Wild Raspberries (1959), a nonsensical cookbook with outrageous recipes. Later he acquired book deals for mainstream publications, including The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again) (1975); the celebrity-studded photo book Exposures (1979); and POPism: The Warhol Sixties (1980), a memoir. All were written with colleagues and assistants, but Warhol, much as he did with his artworks, marketed them as his own. His final book, America, published in 1985, captured the essence of its era. (The Andy Warhol Diaries would be published posthumously, in 1989.)

Image Gallery

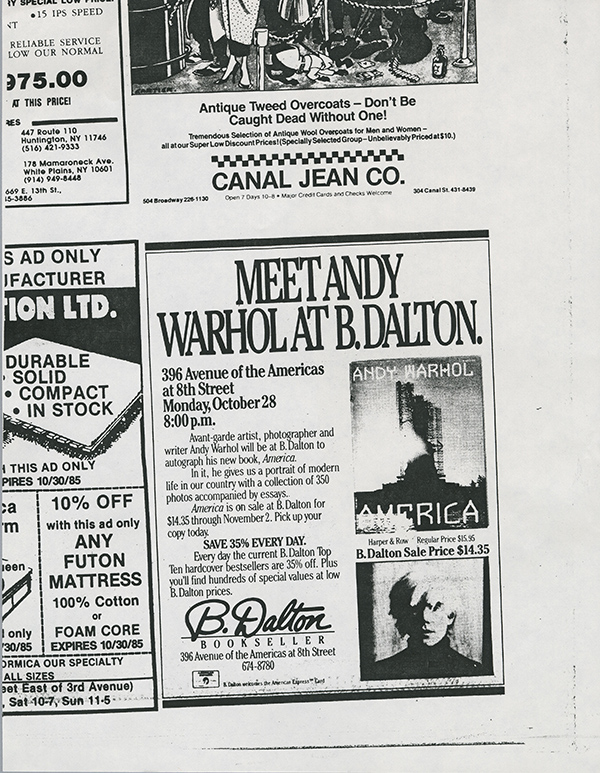

America was unpretentious. “It’ll be a book of photographs with just a little text—maybe just captions,” the artist mentioned in his diary.4 An advertisement for the finished book praises the “Avant-Garde artist, photographer, and writer” for showing readers, “a portrait of modern life in our country.”5 Critics were skeptical of the authenticity of Warhol’s voice, however, as well as his dedication to the project.6 Like Frankenstein’s monster, America was in fact stitched together and given life from existing materials: previously published quotes and hundreds of photographs, both new and old. It was designed to resemble a hybrid of yearbook, zine, and scrapbook.

Two years earlier Craig Nelson, an editor at the publishing house Harper & Row, had corresponded with Warhol to propose America, title as well as content. Historically Warhol had always been open to ideas for his projects.7 Nelson would immediately come on board as the editor of America and wear many hats during its completion and promotion. (He had also secured a deal with the artist Laurie Anderson to publish a book titled United States with the very same team.)8 For the book’s text Nelson gathered existing Warholian passages and drafted his own contributions, which Warhol “fiddled with” later. Supplying photographs for the book become an additional task because, “an awful lot of the pictures turned out to be not that interesting in the archives,” Nelson recalled, and “a lot of my work was actually dragging Andy out to do things to take new pictures for the book to give him a fresher, more interesting look.”9 This ambrosia salad of a project also included photographs taken by Nelson, Christopher Makos, Paige Powell, a paparazzo, and a socialite. Finally the book’s designer had “free rein” in creating the layout, which took her one weekend to complete.10 In the end America would become part of Warhol’s creative output but remain relatively obscure after his death in 1987.

* * *

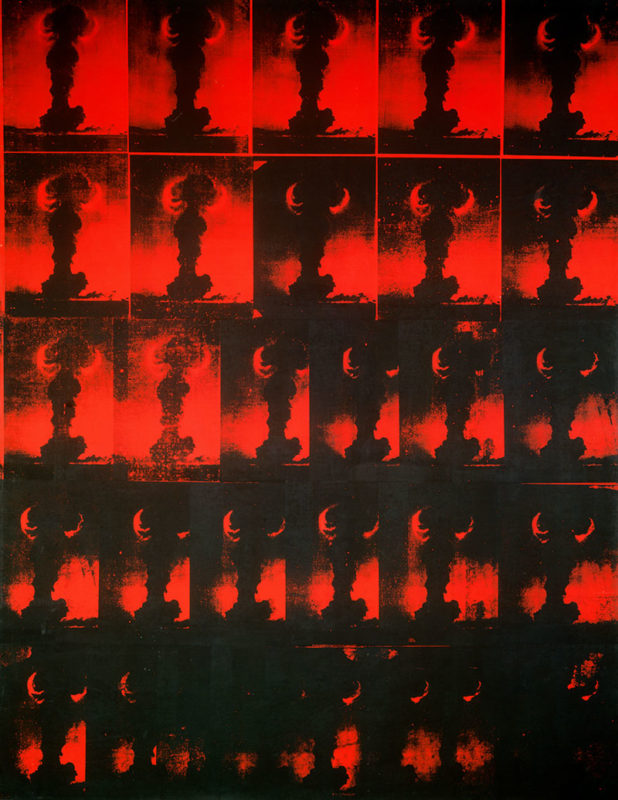

Whether appropriating images or taking original photographs, Warhol acted as a passive observer who amplified the (in)significance of his everyday surroundings. His Pop canvases of the 1960s re-presented press images of current events—including the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, attacks by police on civil rights protestors, and car wrecks and suicides—through the eyes of an emerging queer artist. These images might have attracted him for various reasons, but he understood their power to rattle viewers, even himself. For example, on August 6, 1945, Warhol’s seventeenth birthday, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, killing vast numbers of people and leading to Japan’s surrender.11 The unforgettable image of the mushroom cloud produced would perhaps haunt the artist, as it was depicted by him once, two decades later, repeatedly silk-screened in black ink on a red canvas.

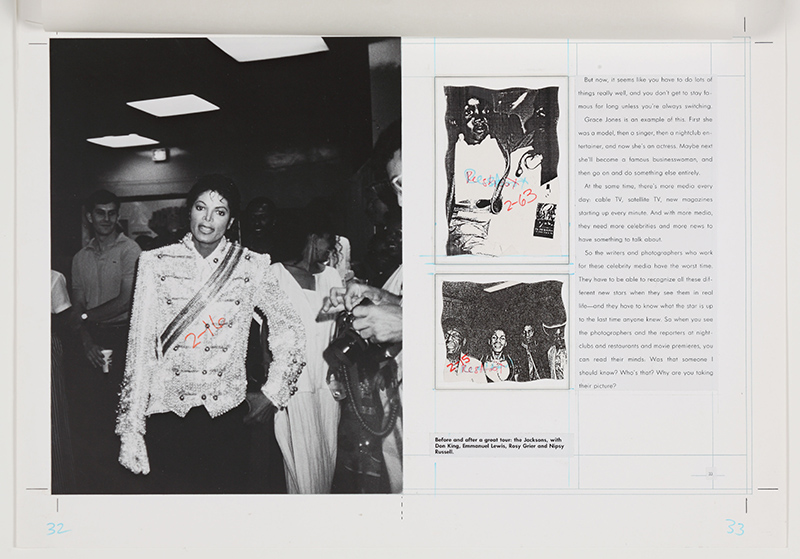

The chapters in America divide the photographs into sections, most titled after popular magazines. For example, “People” is filled with photos of (still) well-known celebrities, including Dolly Parton, Mick Jagger, and Grace Jones. The chapter “Physique Pictorial” features wrestlers, beauty queens, and male strippers. Other chapters include “Life,” “Vogue,” and “Natural History.” The hardiest chapter, “National Geographic,” includes photos from travels across the country, from New York to Los Angeles. The images appear as clichéd snapshots, similar to those of a tourist, of places like the White House, the Twin Towers, and the Paramount Pictures studios in California (the latter likely a tribute to Warhol’s then boyfriend, Jon Gould, who was an executive at Paramount). Images in the book echo the American subject matter of other Warhol works, including the Statue of Liberty, the Washington Monument, and the Empire State Building, the star of the eight-hour film Empire (1964), which consists of a stationary shot of the building from dusk until dawn.

Passages throughout the book take on beauty, consumerism, and fame, just as one would expect. Yet new subjects are also covered—including poverty, immigration, and technology—all with an opinionated tone. For example: “Every year there’d be a new scientific discovery or a new invention, and everyone would think the future was going to be even more wonderful than ever. . . . Now it seems like nobody has big hopes for the future. We all seem to think that it’s going to be just like it is now, only worse.”12 Or: “This country is so rich. And I think I see more homeless people on the street every month. How can we let this keep happening?”13 Regardless of Nelson’s uncredited contributions, like those of others before him, the entire text possesses Warhol’s relevant opinions and timelessness, ringing true even thirty-five years later.

* * *

America had a hectic promotional tour with scheduled appearances by the artist. With the recent Olympic Games hosted in Los Angeles, a renovation of the Statue of Liberty, and the humanitarian hit ballad “We Are the World,” American culture was on everyone’s radar. From October through December 1985 Warhol traveled to Washington, DC, Detroit, Boston, Chicago, and Dallas. At a signing at the Rizzoli bookstore in New York, a young woman with a copy of America, meant to be autographed, quickly yanked off Warhol’s platinum wig and tossed it from the store’s balcony down to an accomplice, who fled. Warhol quickly pulled the hood from his jacket over his head. Humiliated but committed to the project, he stayed and continued to sign copies of the book. He was left shaken and distressed over the incident.14 “It was shocking. It hurt. Physically. And it hurt that nobody had warned me. . . . So that’s that and now I never have to talk about it again,” he later confided to his diary.15

Image Gallery

Photocopy of an ad for a book signing at B. Dalton, New York, October 28, 1985. The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. TC451.52.8

Warhol was clearly upset. During the preparation and completion of America, his private life was complicated. In February 1984 Jon Gould, his live-in boyfriend, was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and diagnosed with AIDS. Warhol, who may not have been completely informed about Gould’s health, had feared catching the disease based on what he knew about it.16 The artist had been shot in 1968 by a would-be assassin and continued to have various ailments throughout the rest of his life. Known for avoiding medical doctors, he tended to his health and well-being through personal trainers, magic crystals, and “popping into church.”17

By 1985 Gould, a closeted gay man, had distanced himself from Warhol and moved back to Los Angeles. That summer AIDS gained mainstream visibility when the actor Rock Hudson announced that he had contracted the disease; he died of complications of it in October. By then Warhol was well aware of the epidemic given what he had witnessed. Gould passed away on September 18, 1986, at the age of thirty-three, blind and weighing just seventy pounds. Warhol left this out of his diary, noting a few days later, “And the Diary can write itself on the other news from L.A., which I don’t want to talk about.”18 In America, Gould appears in photos, uncredited, at Warhol’s recreational compound in Montauk, on Long Island, where the two had spent happier times together.

* * *

Death was in the air. Parallel to the America project, Warhol was commissioned in 1984 by the art dealer Alexander Iolas to create a Last Supper series consisting of more than one hundred works, all depicting aspects of Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic mural, painted from 1495 to 1498 in the refectory of Milan’s Santa Maria delle Grazie convent. In January 1987 twenty-two of Warhol’s Last Supper works were exhibited in a former monastery directly across the street from the original. The biblical narrative, one that he had known since childhood, features Jesus Christ at a final gathering before his crucifixion.19 The scene foreshadows the ascension of Christ, yet Warhol’s version seems to adumbrate his own unexpected demise. The artist died in New York on February 22, 1987, due to complications following surgery to remove his gall bladder.20

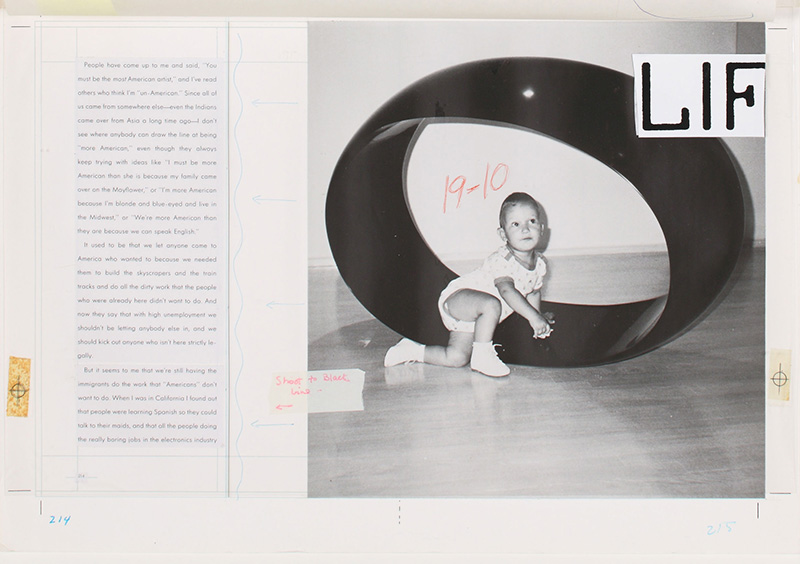

The final chapter of America is titled “Life,” and the text and accompanying images conclude with hope for the future. According to one critic, “As a book of photographs, America is entirely successful and in keeping with Warhol’s output as a painter and filmmaker. Potent one day, disposable the next, Warhol’s camera eye delivers a cynical but deadly accurate picture of our times.”21 The photos in “Life,” which depict toddlers and children, do not appear to partake of this cynicism. In strollers, on a parental lap, or playing together, the children are often accompanied by artworks. One child poses beneath a large circular sculpture. Another wears a Keith Haring T-shirt featuring a cartoonish illustration of a crawling child with dashed vertical lines around the body. This image is known as the Radiant Baby, and Haring stated, “The reason that the ‘baby’ has become my logo or signature is that it is the purest and most positive experience of human existence.”22

Image Gallery

The pairing of the child and Haring’s baby image emphasizes the importance of life but also of artists. Warhol’s America includes images of young, emerging artists of the moment—including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Francesco Clemente, Eric Fischl, Jedd Garet, Keith Haring, Victor Hugo, Kenny Scharf, Julian Schnabel, and John Sex—many of whom he befriended and even collaborated with.23 In September 1983 the Black graffiti artist Michael Stewart died while in the custody of the New York City Transit Police. Warhol noted that Haring was upset, “ranting and raving about this black graffiti artist that’s in the papers now because the police killed him—Michael Stewart. And Keith said that he’s been arrested by the police four times, but that because he looks normal they just sort of call him a fairy and let him go. But this kid that was killed, he had the Jean Michel look—dreadlocks.”24 Many artists at the time made works that protested the unjust killing, including Haring in 1985. Warhol understood what it means to be young, creative, and different in America. He had also witnessed the destruction of so many creatively chaotic peers and followers, and yet he survived to achieve his own version of the American Dream. (His parents immigrated to this country via Ellis Island with dreams of a better life.)25 Warhol concludes the book with a hopeful message: “We all came here from somewhere else, and everybody who wants to live in America and obey the law should be able to come too, and there’s no such thing as being more or less American, just American.”26

A consideration of Warhol’s final decade, in both his personal and professional lives, reveals a contemplative older queer man pondering life in the United States. Many of the social and political issues of the day might not have affected him directly, but he certainly observed and reflected on them through his artistic production, including America. His admiration for his own generation of artists as well as those that followed was well known and continued through his legacy, a foundation established after his death.27 The artists featured in Fantasy America are representatives of a new generation who continue to question life and explore their own experiences and surroundings. Whether responding to social and political concerns or pop culture, Faustine, Olujimi, Silano, Tsabar, and Wise depict life and death, resilience and vulnerability, isolation and community, joy and sadness, fame and failure, dreadfulness and beauty, as well as (in)justice, gender, sexuality, and otherness to weave a fantasy America that is not more or less American but just American.

Endnotes

- Andy Warhol, America (New York: Harper & Row, 1985), 8. ↵

- Katherine Sonntag, “Success Is a Job in New York,” Glamour, September 1949, unpaged. ↵

- Blake Gopnik, Warhol (New York: Harper Collins, 2020), 293 ↵

- Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, ed. Pat Hackett (New York: Warner, 1989), 530 (September 24, 1983). ↵

- Photocopy of advertisement found in correspondence from Craig D. Nelson to Warhol, Time Capsule 451, The Andy Warhol Museum Archives. ↵

- Lucy Mulroney, Andy Warhol, Publisher (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 137 ↵

- Gopnik, Warhol, 227. In 1961 the aspiring art dealer Muriel Latow allegedly came up with the Campbell’s Soup idea in exchange for a fifty-dollar check from Warhol. In 1964 the curator Henry Geldzahler suggested flower paintings. Gopnik, Warhol, 385. ↵

- Mulroney, Andy Warhol, Publisher, 138–39 ↵

- Craig Nelson, quoted in Mulroney, Andy Warhol, Publisher, 146, 147. ↵

- Barbara Richer, quoted in Mulroney, Andy Warhol, Publisher, 150. ↵

- Estimates of the number of deaths at Hiroshima vary widely, from around 70,000 to around 140,000, out of a population of roughly 255,000. Alex Wellerstein, “Counting the Dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 4, 2020, https://thebulletin.org/2020/08/counting-the-dead-at-hiroshima-and-nagasaki/. ↵

- Warhol, America, 184–86. ↵

- Warhol, America, 194. ↵

- Mulroney, Andy Warhol, Publisher, 152. ↵

- Warhol, Andy Warhol Diaries, 689 (October 30, 1985). ↵

- Gopnik, Warhol, 890 ↵

- John Richardson, “The Secret Warhol: At Home with the Silver Shadow,” Vanity Fair, July 1987, 125. According to Kenneth Wahrenberger, in his unpublished paper “‘Popping into Church’: Andy Warhol, the Catholic Observer,” Warhol’s diaries mention him going to church fifty-six times, on fifty-six different days. ↵

- Warhol, Andy Warhol Diaries, 760 (September 21, 1986). ↵

- Gopnik, Warhol, 901. ↵

- Iolas would die from complications of AIDS shortly after, on June 8, 1987. ↵

- Larry Frascella, “Andy Warhol’s America” (review), Aperture, no. 103 (Summer 1986): 14. ↵

- From Andrea Codrington, “Keith’s Kids,” Sphere Magazine, 1997, available at https://www.haring.com/!/selected_writing/keiths-kids. ↵

- Many would experience some degree of success but die too young: Basquiat from an overdose at twenty-seven; Haring, Hugo, and John Sex from AIDS, along with their contemporaries Peter Hujar, Antonio Lopez, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Paul Thek. ↵

- Warhol, Andy Warhol Diaries, 533 (September 29, 1983). In 2019 Chaédria LaBouvier curated Basquiat’s “Defacement”: The Untold Story for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, an exhibition centered on Basquiat’s work commemorating Stewart’s death, originally painted on the wall of Haring’s studio. Haring made Michael Stewart—USA for Africa in 1985. ↵

- Matt Wrbican, “J Is for Julia,” in A Is for Archive (Pittsburgh: Andy Warhol Museum; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), 133. Julia entered the United States on June 21, 1921. Andrej arrived on November 16, 1912, according to a declaration of intention owned by Donald Warhola. ↵

- Warhol, America, 223. ↵

- According to The Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts: “His will dictated that his entire estate, with the exception of a few modest legacies to family members, should be used to create a foundation dedicated to the ‘advancement of the visual arts.’” “Foundation Past and Present: Creative Impact,” https://warholfoundation.org/foundation/index.html. ↵