Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens

The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, ca. 1615

Oil on panel

Image Gallery

Pivi’s manicured landscapes featuring captivating creatures represent more than just face value. Pop artist Andy Warhol allegedly told a journalist, ‘If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.’5 While the statement apparently dismisses artistic depth in favour of superficiality, Pivi’s work presents similar questions because her intertwined connection between man and beast takes place within a manufactured world that has deeper significance than just serving as a setting for beautiful and baffling photographs. Pivi was once called the ‘high priestess of Cockaigne’, a medieval fantasy realm filled with impossible excess and imaginary pleasures;6 however, she works very much in reality and in the present. For example, the series Yee-haw (2015) began with an essentially straightforward concept: releasing horses inside the Eiffel Tower. A simple idea yet complicated in execution. It is like a wedding cake: people know what it is, but do not often know how to make one. In Yee-haw the equine animals and the Parisian monument align in beastly matrimony.

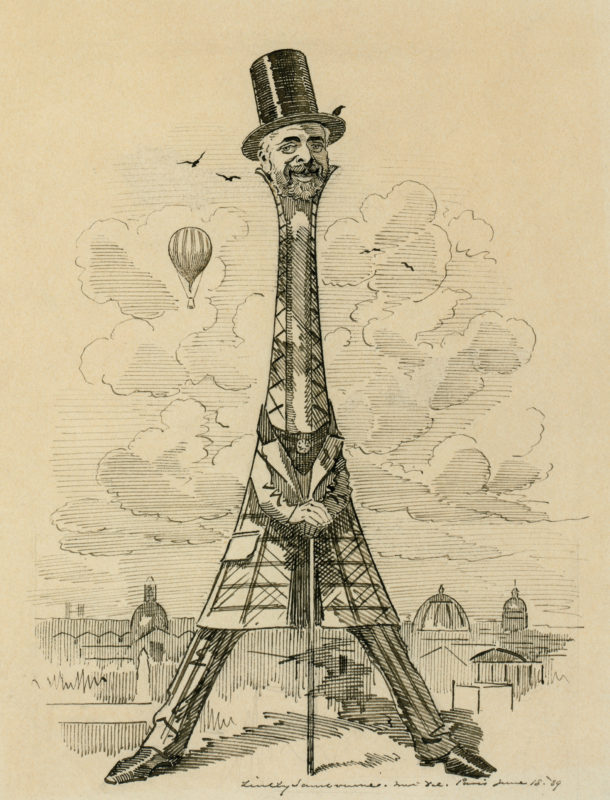

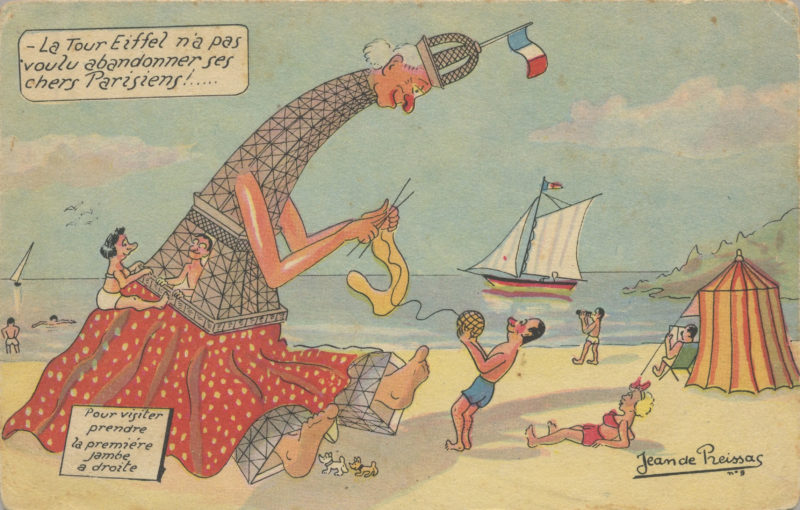

The Eiffel Tower was originally built for the entrance of the Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair hosted in 1889. The 1,000-foot-high iron structure was funded and designed by the engineer Gustave Eiffel (also credited for designing the interior structure of the Statue of Liberty). Although conceived as a temporary construction, through negotiations it remained in place and has since become a pilgrimage site of national pride, celebration, veneration, protest, suicide, mourning, commemoration and, most of all, tourism.

Image Gallery

The elephant from the Cirque d' Hiver-Bouglione on the first floor of the Eiffel Tower on July 4, 1948.

Pivi’s proposal became possible with an invitation from Virginie Coupérie-Eiffel, the great-granddaughter of the tower’s creator. A champion rider and event organizer herself, she asked Pivi to design the annual poster for Paris Eiffel Jumping, an international equestrian competition that takes place near and around the tower.7

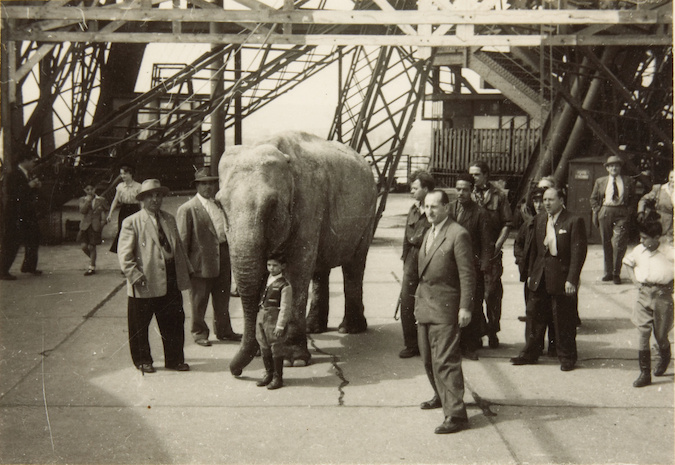

Historically horses have been a constant presence around the area, mostly as a mode of transportation prior to the advent of the automobile. Early photos show horse-drawn carriages around the tower. In Yee-haw, as with previous projects, Pivi removes humans from the photo-performance and confines our participation to the role of passive observer. Four professionally trained horses, two white and two brown, spent several early mornings being photographed on the tower’s first level platform before the site opened to the general public. Transformation quickly ensued as the horses blended with the metal columns, at times becoming almost one and the same, depending on the sunrise and the camera angle. Pivi acknowledges that such a setting ‘can highlight the design of the animal, as if there could have been a designer’.8 The four riderless horses swirl in joy, recreation and liberation, animals and tower uniting in a single spectacle. Surprisingly the site is already known for odd encounters, such as when a circus elephant visited the first level platform in 1948 and when farmers grazed approximately 250 sheep at its base in 2014, in protest at what they saw as the government’s over-protection of hungry wolves.9

The project’s title, Yee-haw, is an expression of excitement related to the classic American ‘Wild West’. Cartoons, films and literature stereotypically depict a male cowboy yelling ‘yee-haw!’ while mounted on his steed. Pivi’s title hints at the absent riders, yet also links the work to early French exposure to cultural Americana. In 1889, at the same time as the Exposition Universelle, horseman and impresario Buffalo Bill Cody was touring through Europe with his ambitious and theatrical Wild West Show. In Paris it rivalled the world’s fair in popularity and spectacle. While Cody embellished life in the American West, then still a colonized frontier, he did in fact introduce a diverse cast that included Native Americans, Mexicans and women, as well as North American wildlife including buffalo, mustangs, mules, bears, moose, elk and Texas Longhorn cattle. The show involved races, riding, re-enacted battles and exaggerated horseplay, (somewhat less decorous than today’s Paris Eiffel Jumping). Dazzled by the exoticism, famed French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822–99) visited the grounds of the Wild West Show and spent hours observing the performers and animals, resulting in over fifty known sketches and paintings.10 Cody even posed for a portrait riding on a white horse. For Bonheur, Cody and his show represented unrestrained freedom and independence (that is to say, the essence of ‘yee-haw!’). As a celebrated animal painter, Bonheur admired the natural world but also enjoyed the one that Cody fabricated around it, in that instance the mythology of the American West and its trappings. Pivi too is enamoured by nature, as well as by the world that mankind has constructed, which in her eyes, like the Eiffel Tower full of horses, is very much alive.

Image Gallery

Rosa Bonheur

Col. William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) (1889)

oil on canvas

From monuments to mattresses, Pivi anthropomorphizes inanimate objects through unassuming display. They too become a living organism in her practice. Among the plethora of man-made stuff whose creation and purpose she reconsiders are the thousands of objects that make up Guitar Guitar (2001). Pivi inventoried and coupled identical pairs of objects like Noah filling his Ark. Installed only twice (!), among the myriad items Pivi included were two automobiles, two motorcycles, two exercise bikes, two football tables, two lamps, two Hello Kitty toasters and, two Mickey Mouse balloons. All laid out, non-functioning and standing in for the absence of humans, they too—much like Pivi’s animals—are re-created through her imagination.

For a new project, in production at the time of writing, Pivi is collecting hundreds of pairs of shoes. A decade ago, the world’s oldest known leather shoe was discovered in an Armenian cave. The 5,500-year-old tanned leather shoe reveals our long-term relationship with footwear, from necessity to narcissism.11 Also tracing our steps, though in more modern terms, Pivi’s project Untitled (shoes) (2022), involves over one hundred pairs of brand-new shoes each with a matching identical pairs, being worn by volunteers and then returned to the artist, before finally being secured on the walls of a museum like trophies, their soles mounted onto the wall’s surface and lined up two by two, in a grid. For example, two pairs of blue satin jewelled Manolo Blahnik heels, made popular in the TV show Sex and The City, will join a collective of dozens of other brands, styles, shapes, colours and materials, from animal leather to industrialized rubber to woven canvas. Each of the worn pairs, bearing their wear and tear like scars, will act as a diary of each individual’s daily rituals from the commencement of the project to the moment of being reunited with their matching unworn pair in Pivi’s installation. These fetishized objects—conceptual effigies of man and material—resemble the displays found in anthropological museums.

There is a phrase about ‘walking a mile in someone else’s shoes’ to better understand their experience or perspective; Pivi, however, goes one ‘step’ further by literally showing us the actual shoes worn by people around the world. The degree of wear and tear is highlighted when placed alongside their pristine partners. By retiring the shoes for the sake of art, Pivi con-siders the superficiality of certain types of footwears and their design. She may be depriving them of their function, yet the shoes collectively communicate the personal style and hours of human labour involved in this participatory project. The artist states, ‘Art is the thing that can change the way people think and perceive…It’s like an exchange of communication—sharing a large amount of information in a very condensed time.’11 The sneakers, sandals, high heels, loafers and array of various other types of footwear collectively tell a creation story, Pivi’s creation.

Pivi also spots a dilemma in the creation process: can one go too far? Absolutely not. Her installation Untitled (muskox) (2008) summarizes the dichotomy of life and death in the twenty-first century. Yet another strategic doubling, it couples a muskox and a mound of coffee beans. Beast and beans, both altered by human intervention, make a formidable, dark monument of fur and fragrance. This relatively unknown bovine is surrounded by thousands of tiny roasted coffee beans, meticulously piled as high as naturally possible. The work is a vanitas still life, pointing to the ephemerality of modern man (who is, yet again, unseen). The muskox and the coffee make an evocative banquet for human survival. Muskoxen are Arctic natives with shaggy hair and curved horns, and emit a pungent odour during mating season. Living in herds, they are resilient mammals that can endure extreme climates. In 1902 one was introduced to New York’s Central Park Menagerie (now Zoo), along with a walrus, by the infamous explorer Robert Peary.12 Muskoxen have also been a sustainable resource for Inuit and Indigenous communities in Canada, Greenland and Alaska. In 1917 another Arctic explorer advocated them as an American meat source, but the endorsement failed.13 Today muskoxen lack such a public platform but Pivi’s artwork gives them new visibility within a sequence of images of exotic creatures (ostrich, alligator, donkey, leopard, performing horses), paired with manufactured goods.

Coffee has appeared in Pivi’s practice on more than one occasion (One cup of cappuccino then I go, 2007; and It’s a cocktail party, 2008). Far more common than muskoxen, coffee consumption can be found in many cultures, especially in Pivi’s native Italy. Coffee beans, the processed seeds of the coffea plant, are specifically grown in warm equatorial regions between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. This curious pairing— hot and cold; large and small; hard and soft; stimulated and sedated; sterilized and fertile—aligns with Pivi’s reconsideration of the lifecycle of living and industrial matter. Coffee is valued and stimulates us; however, here, it remains unbrewed and failing to fulfill any purpose. The muskox, very much dead and now lacking its musky smell, stands alone, committed to a life as memento mori. Combined, the two function very much like an existentially loaded poop emoji: ‘shit happens’.

Through her visions of wearing out hundreds of ready-made shoes or of beautiful horses claiming spaces where they should not be, Pivi materializes a brand-new world that is unconventional and entertaining, but also thought-provoking once you get past the surface. Yee-haw has become Pivi’s final photo-performance with live animals. However, the artist did have one further unrealized creation: placing a giraffe on top of a skyscraper. Just imagine that! It reminds me of a joke: How many animals can jump higher than a skyscraper? All of them, skyscrapers can’t jump. Perhaps not, but with Paola Pivi anything is possible.

Endnotes

- King James Bible, Genesis 1:24–31. ↵

- Interview with Jeff Rian, 2006, https://www.perrotin.com/artists/Paola_ Pivi/10#text. Accessed 30 March 2021. ↵

- Interview with Oliver Basciano, ArtReview, originally published October 2013, https://artreview.com/october-feature-paola-pivi/. Accessed 30 March 2021. ↵

- Jacqueline Terrebonne, Galerie Magazine, 26 April 2019, https://www. galeriemagazine.com/paola-pivi-perrotin/. Accessed 30 March 2021. ↵

- Gretchen Berg, ‘Andy Warhol: My True Story’, East Village Other, 1 November 1966; reprinted in Kenneth Goldsmith, Reva Wolf and Wayne Koestenbaum, I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews: 1962–1987 (New York, 2004), p. 90. ↵

- Massimiliano Gioni, ‘We Want it All’, in Paola Pivi (Galerie Perrotin / Damiani, Bologna, 2013), p. 145. ↵

- See https://pariseiffeljumping.com/en/index.html. Accessed 30 March 2021. ↵

- Nick Compton, ‘Horsing around: Paola Pivi reaches new heights at the Eiffel Tower’, Wallpaper, 5 June 2015, https://www.wallpaper.com/art/horsing-around-paola-pivi-reaches-new- heights-at-the-eiffel-tower. Accessed

30 March 2021. ↵ - In 1948 an elephant named Marie visited the first platform as a publicity stunt. In 2014 French farmers herded sheep to the Eiffel Tower in protest at wolf attacks on their livestock. See ‘Eiffel Tower Surrounded By Sheep As French Farmers Protest Wolf Attacks’, Insider, 27 November 2014, https://www.businessinsider.com/afp-sheep-flock-to-eiffel-tower-as-french-farmers-cry-wolf-2014-11. Accessed

30 March 2021. ↵ - Steve Friesen, ‘A Match Made in Paris’, True West Magazine, February–March 2021, https://truewestmagazine. com/article/a-match-made-in-paris/. Accessed 30 March 2021. ↵

- 12. Kathryn O’Regan, ‘Italian artist Paola Pivi invites you to take a break from the world and share a giant mattress with strangers’, Sleek Magazine, 3 April 2019, https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/paola-pivi/. Accessed 30 March 2021. ↵

- 13. ‘Peary Party’s Rare Animals. Explorers Bringing Back Muskox, Walrus, and Eskimo Dogs for Central Park Menagerie’, New York Times, 21 September 1902. Unfortunately, Peary also trafficked humans. Returning on one expedition he docked his ship, The Hope, and sold tickets to board and witness six ‘Eskimos’ and a ‘100-ton meteorite’, which had provided iron to the Inuit before Peary’s plunder. The captives and meteorite were then acquired by the American Museum of Natural History as specimens. ↵

- ‘Stefansson Urges Muskox for Food’, New York Times, 23 March 1918. ↵