EssayThe Pop Politics of Warhol’s Presidential Portraits

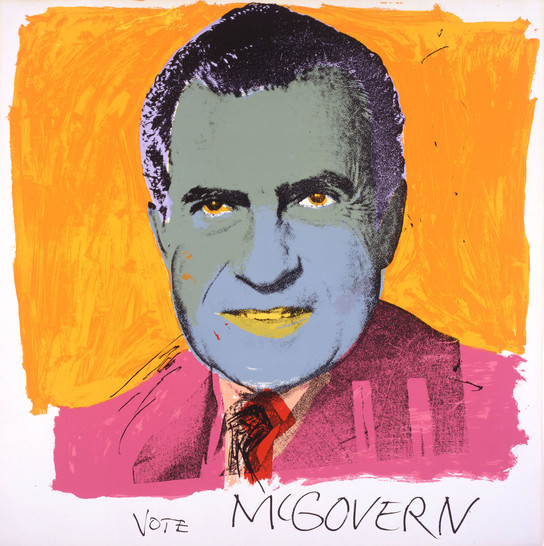

Andy Warhol, Vote McGovern (1972)

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection

Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

1998.1.2399

Image Gallery

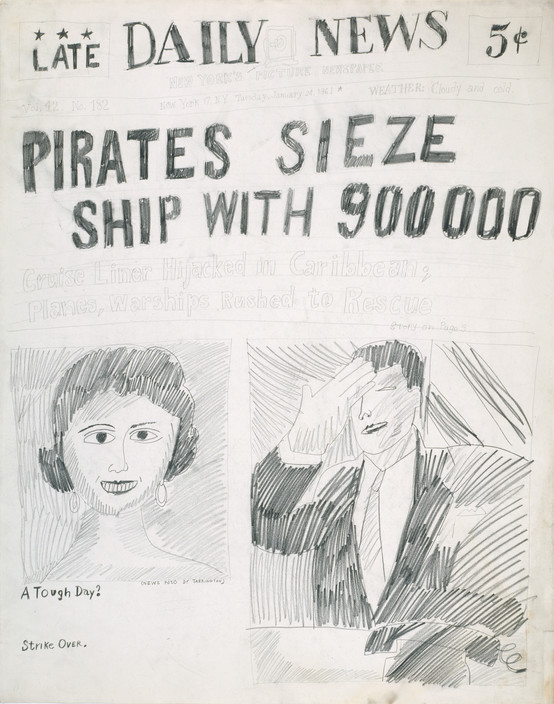

In 1968, Warhol completed an unusual project titled Flash—November 22, 1963, an unbound book consisting of screenprints and teletype reports revolving around Kennedy’s infamous assassination. Rather than taking the straightforward route of appropriating a press photograph of Kennedy, Warhol used Kennedy’s 1960 campaign poster and an image of Kennedy on a television screen as his source material.2 The viewer therefore does not see Kennedy directly so much as the depiction of Kennedy in the media. On the subject of the Kennedy assassination, Warhol later explained, “What bothered me was the way the television and radio were programming everybody to feel so sad.”3 With Flash and the Jackie portraits, Warhol investigated those media programming efforts.

Image Gallery

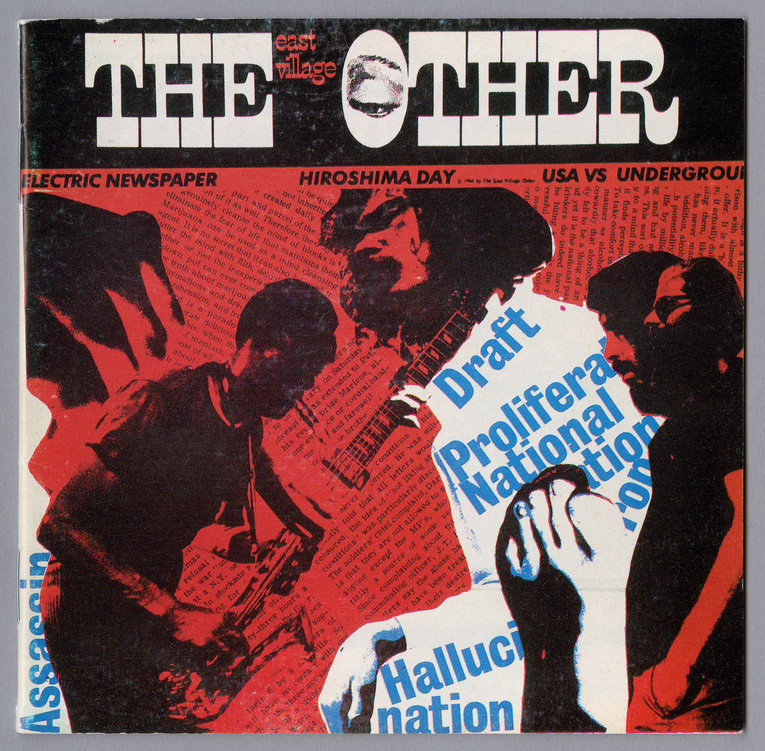

Warhol never created a portrait of Lyndon Johnson, unless you count an obscure Polaroid depicting a framed photograph of Johnson behind a white plaster monkey. But Johnson’s presence is heavily implied in some of Warhol’s portraits of Jackie Kennedy, in which Warhol appropriated an infamous photograph of the stunned soon-to-be-former First Lady standing next to Johnson on Air Force One as he is sworn in as the country’s thirty-sixth president. A few years later, Warhol participated in the recording of Electric Newspaper, Hiroshima Day, USA vs. Underground, a 1966 album created by an underground newspaper called The East Village Other. Other contributors included Superstars and friends of the Factory such as Gerard Malanga, Ingrid Superstar, The Velvet Underground, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, and Ed Sanders.4 The album is a radical auditory collage in which songs, poems, chants, and gossip overlap with excerpts from radio coverage of the wedding of Luci Johnson, President Johnson’s youngest daughter. Warhol himself contributed eleven seconds of silence.

Image Gallery

Warhol’s literal silence when it comes to Johnson’s presidency may seem puzzling, especially since Johnson held office during such important years in Warhol’s career. However, when Warhol first started to define himself as a Pop artist and experimental filmmaker in the mid-1960s, his work rarely focused on politics so much as media coverage of political issues. He did not paint President Johnson, but he painted the photograph of Johnson’s chaotic swearing-in ceremony. He did not paint civil rights leaders, but he painted one of the most iconic photographs of police brutalizing demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama. He did not paint the Vietnam War, but his film Chelsea Girls includes a monologue parodying the radio reportage of Hanoi Hannah. As Warhol established his oeuvre, focusing on the media—as the connection between pop culture and politics—gave Warhol a buffer and allowed him to avoid making explicitly political statements.

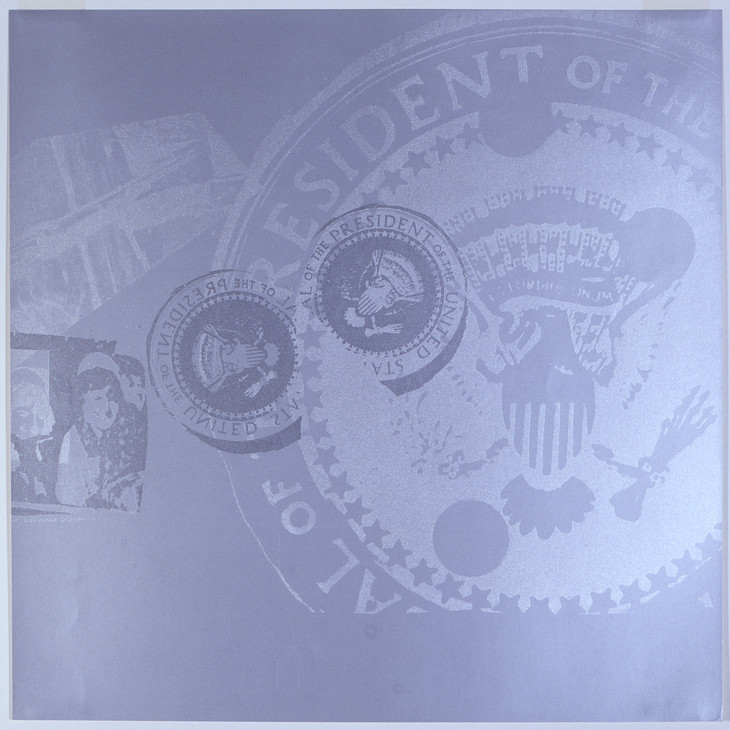

By the 1970s, Warhol was finally ready to start making explicitly political statements. His poster for George McGovern’s campaign, Vote McGovern (1972) is arguably his most legendary presidential portrait. It marked the first time an American presidential campaign commissioned a famous artist to create a poster, and sales of the poster raised about $40,000 for McGovern.5 Considering McGovern’s transgressive support for LGBTQ+ rights despite the efforts by the DNC to remove LGBTQ+ rights from the official party platform, it is notable that he chose an openly gay artist for this commission.6 Of course, McGovern lost the election and Nixon apparently did not appreciate his depiction in Warhol’s portrait. Beginning in 1972, Warhol was audited annually by the IRS, and he was convinced that this was Nixon’s form of revenge.7

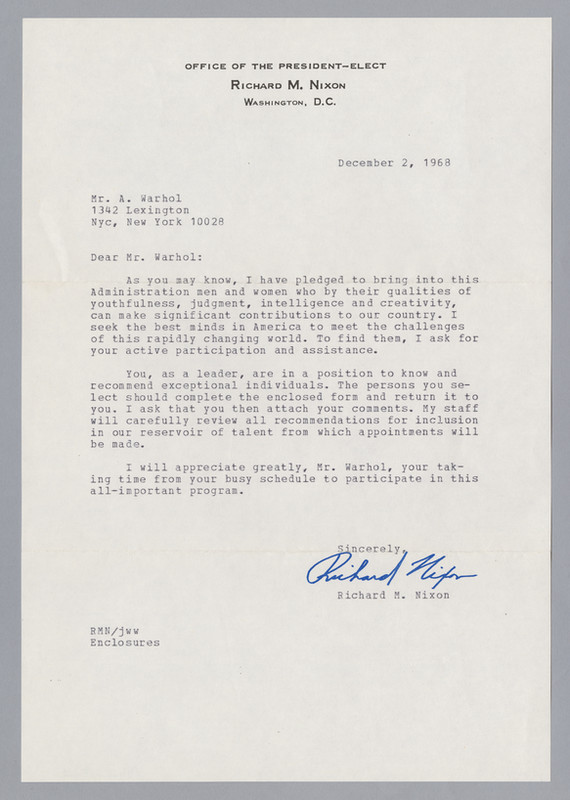

Four years prior to Vote McGovern¸ Nixon unexpectedly reached out to Warhol for help. There is a letter in The Andy Warhol Museum’s archives dated December 2, 1968, with the prestigious letterhead of the “Office of the President-Elect Richard M. Nixon.” The letter begins, “Dear Mr. Warhol: As you may know, I have pledged to bring into this Administration men and women who by their qualities of youthfulness, judgment, intelligence and creativity, can make significant contributions to our country. I seek the best minds in America to meet the challenges of this rapidly changing world. To find them, I ask for your active participation and assistance. You, as a leader, are in a position to know and recommend exceptional individuals.”8 Since the two government appointment forms included with the letter remain blank, it would appear that Warhol never replied, probably because he did not think any of his friends would want to work for the Nixon administration. Nonetheless, the letter indicates that Nixon at one point held a rather high opinion of Warhol, which may have contributed to how insulted Nixon felt when he saw Warhol take McGovern’s side.

Image Gallery

Richard Nixon, Envelope, letter, and two federal government appointment forms (from the Office of the President-Elect Richard M. Nixon to Andy Warhol, no postmark) (1968); The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Gift of Thomas Ammann Fine Art Gallery, Zurich, Switzerland; 1993.1.9.1-1993.1.9.4

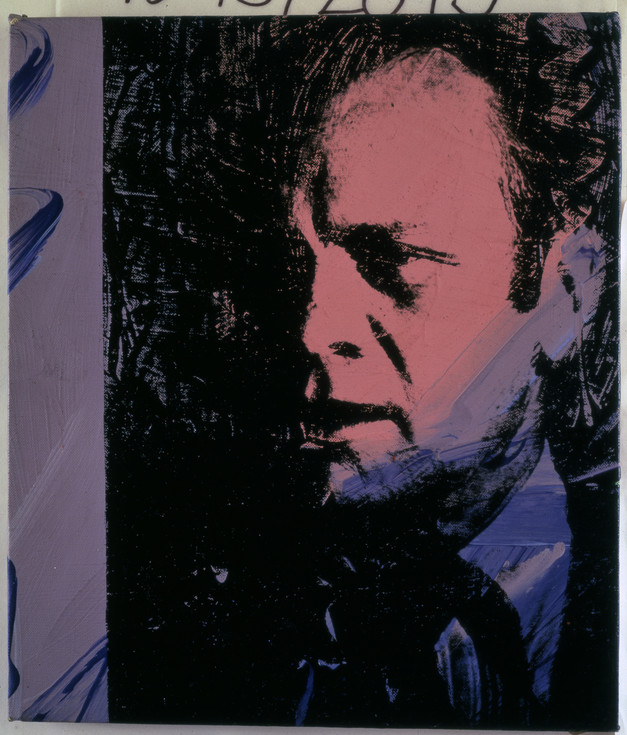

Soon after Nixon’s resignation, Vogue magazine commissioned Warhol to paint a portrait of Gerald Ford for a feature story on the new president in their October 1974 issue.9 A few months later, Ford became the first president to invite Warhol to the White House. On May 15, 1975, Warhol attended Ford’s state dinner in honor of the Shah of Iran. Ford’s invitation likely stemmed from Warhol’s friendships with Ardeshir Zahedi, the Iranian ambassador to the United States, and Fereydoun Hoveyda, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations. These friendships and Warhol’s interactions with Farah Diba Pahlavi at the state dinner eventually resulted in the Iranian royal family commissioning Warhol to paint their portraits in the late 1970s.10

Meanwhile, Warhol inadvertently soured his relationship with the Ford family later in the summer of 1975. After Warhol’s good friend Bianca Jagger met Jack Ford at a disco, Warhol and Jagger returned to the White House to interview and photograph the president’s son for Interview magazine. Interview photographer Dirck Halstead and White House photographer David Kennerly helped document the occasion.11 The resulting photographs released to the press look quite innocent by today’s standards, but at the time some Americans believed that Jack Ford was flirting with a married woman, and in Lincoln’s Bedroom, no less. Jack Ford endured a backlash in the conservative press and caught flak from his own mother. Although he certainly understood that the scandal was overblown, Jack Ford went on to tell Rolling Stone, “I have a hard time reading Andy Warhol’s magazine.”12

Image Gallery

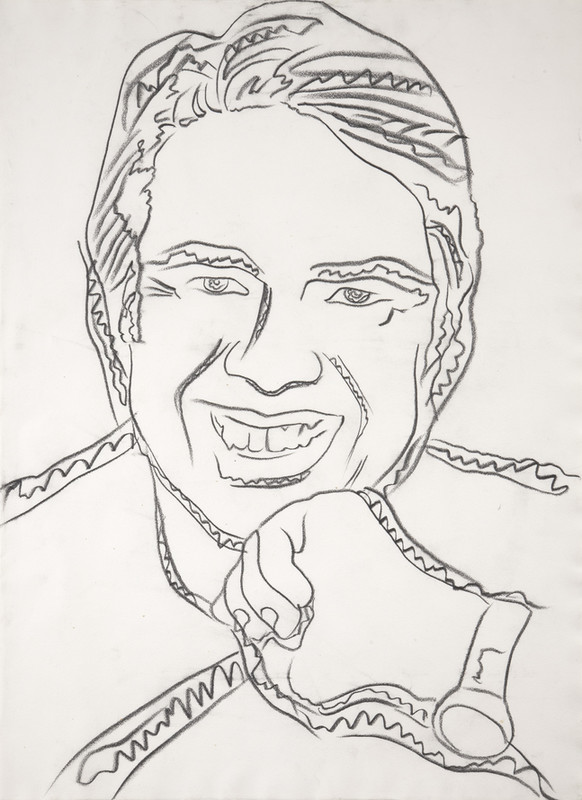

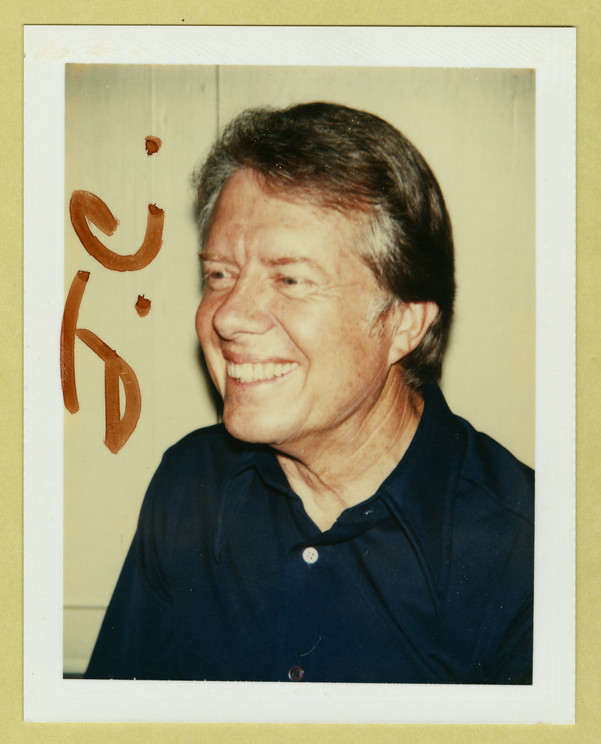

Fortunately, Ford’s successor, Jimmy Carter, was a Warhol fan. In August of 1976, Warhol visited Carter’s peanut farm in Plains, Georgia to photograph the presidential candidate for a poster commissioned by the Democratic National Committee. Warhol later chronicled his time at the peanut farm in his 1979 book, Exposures, writing of the Carters: “They were very normal. We got along very well….Jimmy Carter gave me two big bags of peanuts which he signed. That made the whole trip worthwhile.” Indeed, Carter found the trip to be worthwhile as well; after his election victory he publicly thanked Warhol and fellow artist Jamie Wyeth for their support, stating, “the fact that Jamie Wyeth and Andy Warhol were willing to help me kind of turned the tide.”13

Warhol ended up photographing not just Jimmy Carter but his wife Rosalynn Carter, his daughter Amy Carter, and his mother Lillian Carter during that visit to Georgia. Warhol went on to create three series of portraits of Jimmy Carter. Jimmy Carter I, the poster designed to raise funds for the presidential campaign, shows an uncharacteristically serious Carter almost frowning at Warhol’s camera. But the typically cheerful Carter smiles in the portraits Warhol made after the election, Jimmy Carter II and Jimmy Carter III, the latter of which was included in Carter’s Inaugural Impressions portfolio alongside portraits by Jacob Lawrence, Roy Lichtenstein, Jamie Wyeth, and Robert Rauschenberg. Warhol attended the Inaugural Impressions reception at the White House, where Carter remarked on the change of his expression in Warhol’s portraits: “The first one was frowning and scowling and worrying because I was broke, I had lost some primaries, I didn’t know where I was going to go next…. And now I think it’s very significant that this picture is smiling. And I’m going to try to keep myself smiling and maybe all of you smiling for the next four years.”14 But Carter may have stopped smiling in 1980 when Warhol did a campaign poster for Carter’s primary challenger, Ted Kennedy.

Image Gallery

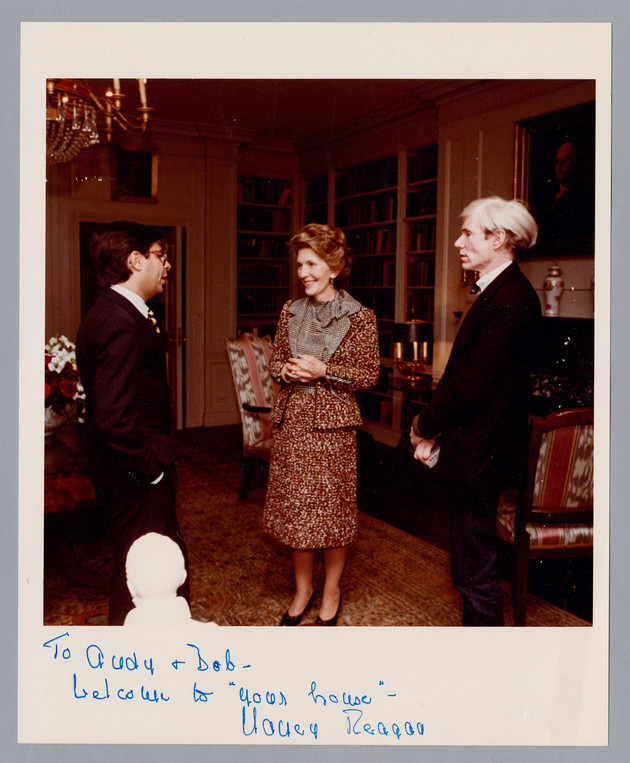

Warhol’s relationship with the Reagans was particularly complex. In 1980, Warhol would have certainly preferred either Ted Kennedy or Jimmy Carter as president over Ronald Reagan. According to Warhol’s assistant Bob Colacello, he turned down two commissions to paint portraits of Reagan in the months leading up to the election.15 However, after Reagan’s electoral victory, Warhol quickly started to warm up to the Reagans. A feature story about Ronald Reagan’s children, Patty Davis and Ron Jr, appeared in the November 1980 issue of Interview, and Warhol attended Reagan’s inauguration in January of 1981.16 Warhol befriended Ron Jr and his wife Doria, attending ballet performances and dinner parties together on a frequent basis in the early days of the Reagan administration. By March of 1981, Colacello had hired Doria Reagan to be his secretary, so there was a Reagan actually working in Warhol’s Factory for a couple of years.17 All of these connections led to Warhol and Colacello returning to the White House to interview Nancy Reagan, who graced the cover of Interview’s December 1981 issue.

Image Gallery

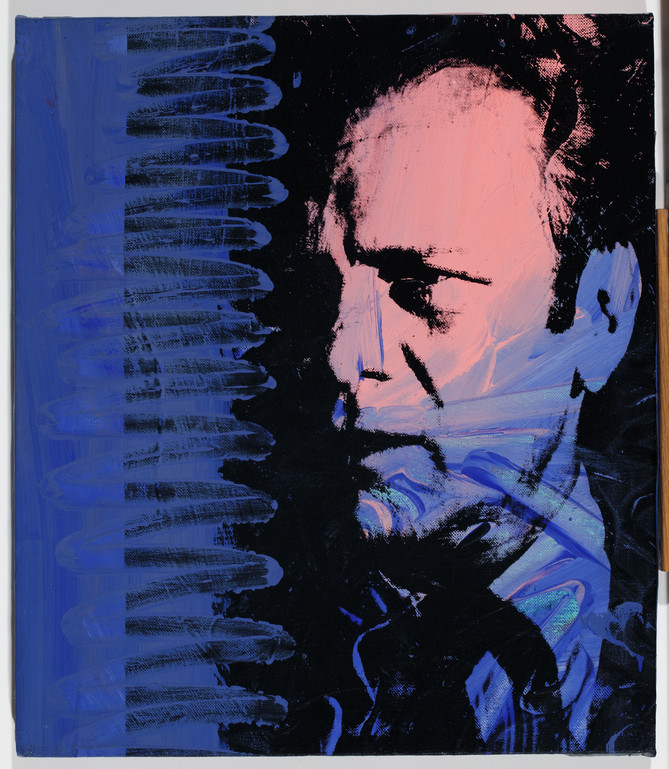

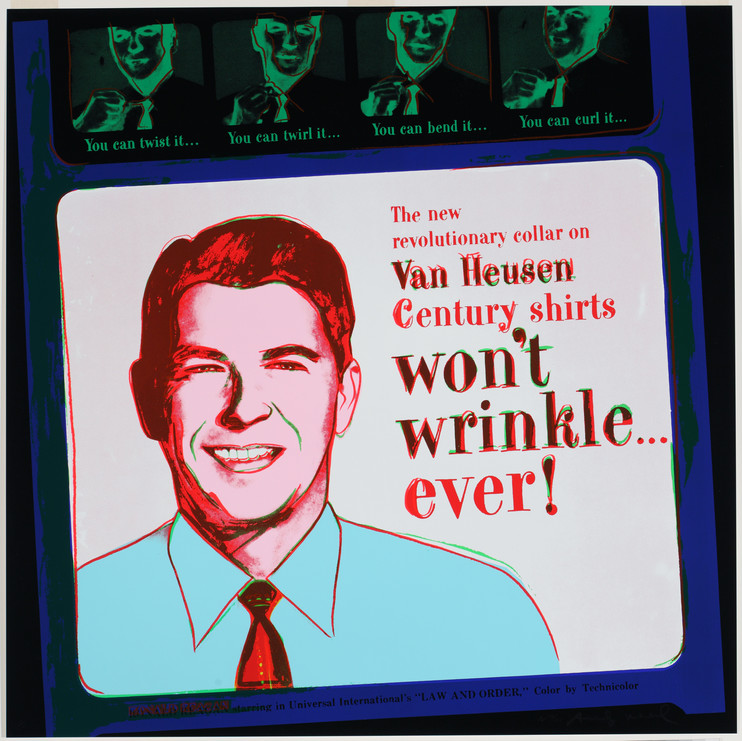

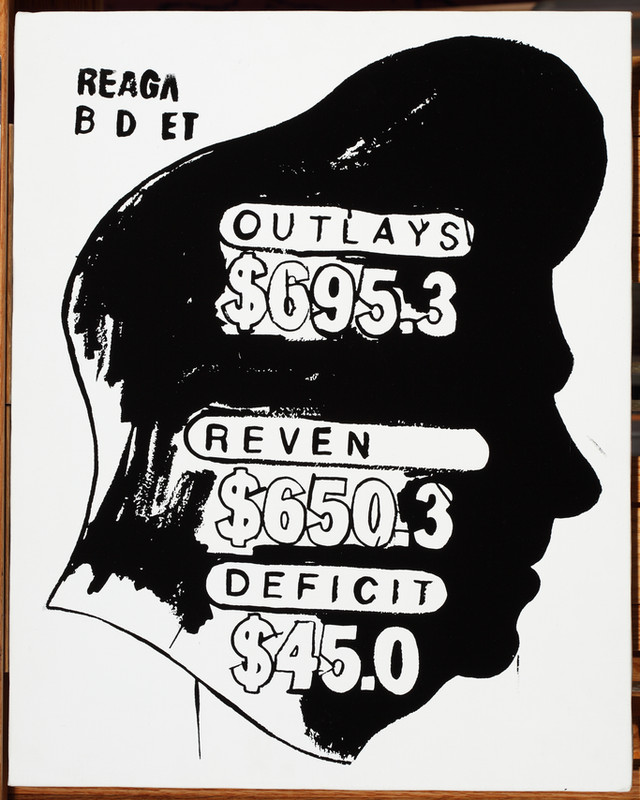

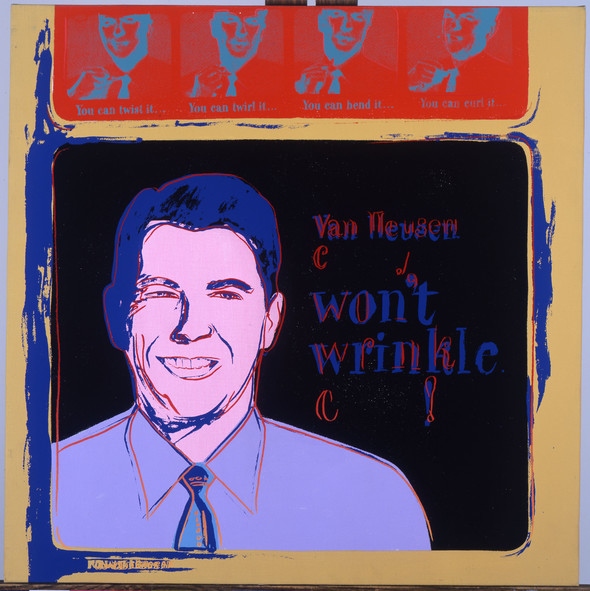

By Reagan’s second term, both Doria Reagan and Bob Colacello had stopped working for Warhol; and with them, Warhol lost many of his connections to the Republican Party. He eventually included images of Reagan in two different art projects, both of which seem to depict the president through a critical lens. Warhol’s Ads series from 1985 features iconic advertisements and corporate logos for brands such as Volkswagen, Chanel, and Apple, as well as celebrity endorsements, like Judy Garland for Blackglama. With Ads: Van Heusen (Ronald Reagan), Warhol pokes fun at Reagan’s Hollywood past, and perhaps even makes the point that Reagan has always been a shill for big business. Reagan Budget (1985–1986), Warhol’s last presidential painting, comes from a rarely exhibited series of small black-and-white paintings of newspaper advertisements and illustrations. In Reagan Budget, the damning numbers of Reagan’s inherently flawed economic plans fill his silhouetted profile. As he had often done in the 1960s, Warhol once again used depictions of the president in the media as his source material; but in these final examples the effect is less neutralizing, as the images show the ways Reagan made money for himself and lost money for the country.

Throughout his life, Andy Warhol closely followed politics in the news; and as his fame skyrocketed, more and more political figures sought him out. His posters for McGovern and Carter constitute both donations and endorsements. His brief friendships with Jack Ford and Ron Reagan Jr show Warhol’s enduring appeal among the youth, even young Republicans. Warhol’s multiple invitations to the White House are a testament to both his stardom and his political influence, albeit his favorite aspects of visiting the White House were the handsome Marines and the American Empire furniture.18 By conventional standards, Warhol was not an activist. He didn’t protest in the streets, he didn’t knock on doors for candidates, and he didn’t even vote. Despite his preference to spend more time in photobooths than voting booths, Warhol’s presidential portraits can convey a great deal about his personal ideology and his unique approach to navigating the political sphere.