Warhol Around the WorldWarhol’s Secret Adventure in the Soviet Arctic

Andy in the Arctic or Умницы from Emily Newman on Vimeo.

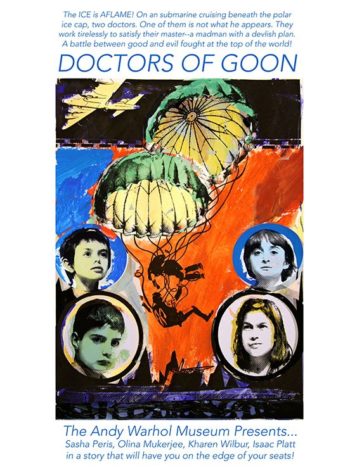

Andy Warhol was never in the Soviet Arctic. But in summer 2015, The Andy Warhol Museum’s education department initiated a collaboration with the Museum of the Arctic and Antarctic in St. Petersburg, Russia. The project was conceived as a parallel initiative in St. Petersburg and Pittsburgh, encouraging Cold War literacy through the study of period pop culture. Students in both places studied politics and films from the 1960s (including the marvelous Ice Station Zebra), conceived their own Arctic Spy Thriller, and made posters (Pittsburgh) and a film trailer (St. Petersburg). Last month, artist Yvegeniy Fiks visited Pittsburgh on the occasion of his museum installation Yevgeniy Fiks: Andy Warhol and The Pittsburgh Labor Files, on view through January 10, 2016. I took the opportunity to show him the film we produced in St. Petersburg and talk about the project’s unexpected outcomes.

Emily Newman: When I showed you our film in Pittsburgh, I thought it was funny that you said something like, “interesting connection between Andy Warhol and the Soviet Arctic….” People in Russia asked me a lot what the connection was, and I had to admit that there wasn’t one.

Yevgeniy Fiks: Well, I think I was thinking in terms of your project: in your project the connection between Warhol and the Soviet Arctic came into being so the connection exists. But in general, there is a strong tangible connection between Warhol and the Cold War, and Pop Art in general and the Cold War. Pop Art being a quintessential American art movement of the Cold War era, with its commodity populism and glorification of consumption. Russian Sots artist Vitaly Komar, for instance, considers late-Soviet Sots Art to be a mirror image of American Pop Art. I think in your project, which is wonderfully playful and imaginative, the absurdity of Warhol’s visiting the Soviet Arctic is a lot of fun. This playfulness makes Andy in your film like the favorite Soviet children’s cartoon character, Cheburashka—someone who is sweet and Soviet-style gender-neutral.

EN: Yes, the conversation that I had with the St. Petersburg museum staff about what I wanted to do before we started was quite vague—I think we all knew that if we got into too many details that we might start hitting barriers, and we didn’t want that to happen. My original idea was to stage a spy thriller inside the museum, to work with children on the Cold War topic in order to familiarize them with the terms of the long-standing relationship between the U.S. and Russia on the world stage. But pretty quickly I was asked not to touch political topics—and eventually I was even asked to de-emphasize Warhol—so we were left with just the shell of an idea: an artist, the Arctic, the ‘60s. Their reasons for being nervous actually make sense. As you know, after the Russian Revolution all churches were demolished or re-purposed—The Museum of the Arctic and Antarctic is the last museum-in-a-church left in the city, and this puts them in an extremely vulnerable position—they cannot risk controversy, and a collaboration with an American museum attracted attention from the outset. But back to the project—I think it’s safe to assume that at least some of the staff were familiar with Warhol, since he is very well known in Russia following the 2000 exhibition at the Hermitage.

YF: I also find it very interesting that with the new restrictions of “no politics and no Warhol” as you put it, your project about politics and Warhol became somewhat akin to Soviet-era children’s television shows, which were playful and sweet. So knowing the background of your project, it makes me think that perhaps the late-Soviet children’s shows that I enjoyed as a child in Moscow, for example, ones about Cheburashka, were perhaps unrealized radical narratives of gender and politics, which became sweet children’s stories because of censorship.

EN: The film is sweet, and one Russian friend called it “vegetarian.” Warhol actually said, when asked, that he wouldn’t have wanted to visit Russia, and who knows what he would have thought of the Arctic, but we can use what we know about Warhol to interpolate what his reaction would be to almost anything. What would Warhol have made of the Soviet Arctic, as it is preserved in this museum? He would have loved it, of course, just like he admitted to loving his trip to China even though he said he hated to travel.

YF: Yes, for sure the “vegetarianism” of the film and its sweetly positive outlook is funny. It’s funny how Warhol is sort of put back into the closet in St. Petersburg’s Arctic Museum! How Warhol got transformed into Cheburashka. And how in a way your project, your film, was put into the closet too in a way. So, being a product of a censorship or restrictions it actually ended up living up to its promise as a project about the Cold War, no?