PittsburghBook Smart

This text by Barbara Klein originally appeared in the fall 2015 issue of Carnegie Magazine, a quarterly publication of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

A revelatory exhibition features a little-known but widely influential chapter of Andy Warhol’s life: redefining the book.

During his pre-Pop days, Andy Warhol would throw coloring parties at his favorite Upper East Side haunt, Serendipity 3. Friends and strangers alike would help him add color to drawings he made for his self-published books—a low-tech version of today’s crowdsourcing campaigns—while downing the shop’s signature “frrrozen hot chocolate.”

Well before the interconnected world of the 21st century, books—mass produced and relatively inexpensive—reached people in ways paintings on a gallery wall could not. And as far as Warhol was concerned, that made it a medium well worth exploring.

Despite rumors to the contrary, Warhol was an avid reader whose literary interests ranged from movie star and Princess Diana biographies to cookbooks, astronomy, plastic surgery, and antiques. A photograph taken in his Montauk, New York, home in the 1970s shows his books arranged spine-in on the shelves.

Throughout his life and work, books, in one form or another and at one time or another, provided the artist with information, inspiration, and income, says Matt Wrbican, chief archivist at The Andy Warhol Museum.

“Publishing was huge during his lifetime,” says Wrbican. “And creating books was vital to his career.”

The first exhibition in the United States to crack the spine on this chapter of the artist’s career opens October 10 at The Warhol and runs through January 10, 2016. Curated by Wrbican, Warhol By the Book features some 300 objects—paintings, drawings, photographs, prints, works never fully realized, and a sampling of books from Warhol’s own eclectic library, including a first edition of the Atkins Diet and a volume on poodles.

Wrbican’s goal: “To represent everything Andy did in regard to books.” No small task considering Warhol’s exploits as an author, commercial illustrator, and publisher. He contributed to 80 books in his lifetime, providing illustrations for mass-market children’s fiction, language instruction, a satirical cookbook, and a book on etiquette.

Ongoing efforts to examine and organize the more than half a million objects in The Warhol’s archives, such as the quirky contents of the artist’s 610 Time Capsules, have helped shape this little-known narrative.

According to Wrbican, the majority of the collection has yet to be sorted, so new discoveries are constantly being made. “Two years ago,” he recalls, “we found original drawings for the book 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy that had never seen the light of day and so the colors are spectacular, stunning.” They are standouts in the exhibition.

Books were the focal point of the 2013 exhibition Reading Andy Warhol organized by Germany’s Museum Brandhorst. Although Wrbican lent his expertise and even penned an essay about Warhol’s unfinished Marilyn Monroe Book for the catalogue, the show never made it to the United States. This gave Wrbican all the more reason to continue exploring the topic, discovering that the artist’s efforts went far beyond any preconceived notions. “The multiplicity of ideas, the amount of work—it’s staggering,” he affirms. “In some ways, books represent Warhol’s most accessible work.”

Kathryn Price, curator of collections at the Williams College Museum of Art in Massachusetts, where Warhol By the Book debuted this past spring, agrees. “The show is revelatory for a lot of people,” she says. “It proves that Warhol interacted with books his entire life and that there were moments when books grounded him.”

Andy the book worm

Perhaps the most significant of those books, the “two biggies” as Wrbican likes to call them, are a family prayer book and a celebrity scrapbook Warhol put together at age 11. The belief is they provided him with both spiritual and earthly comfort as he struggled through a serious childhood illness and then the death of his father when he was just 14.

Andrej Warhola, a construction worker who emigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, scrimped and saved $1,500 so that his son, considered the best bet to support the family, could start hitting the books at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in 1945. Four years later, Warhol graduated with a bachelor of fine arts degree in pictorial design.

A handful of Warhol’s textbooks from college and his days at Pittsburgh’s Schenley High School, as well as several class assignments, are included in Warhol By the Book. Complete with handwritten notes in the margins, underlining and doodles, they provide a glimpse into Warhol’s early interactions with the printed page. They also foreshadow the first chapter in Warhol’s career: successful commercial illustrator.

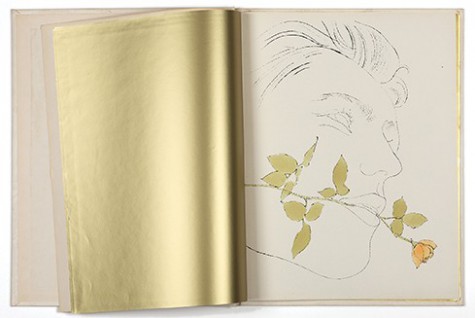

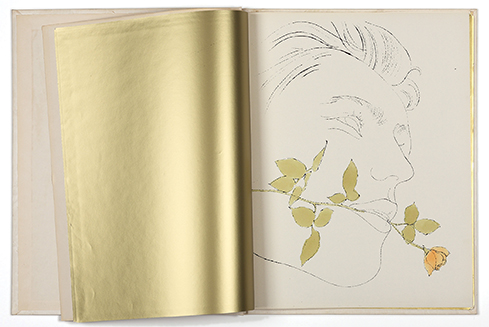

Many unfinished works are highlighted, including this unique maquette for a book made from Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe prints that unfolds to measure nearly 30 feet. Other gems: the mock-up designer’s copy of Andy Warhol’s Index (Book) and A Gold Book.

Other signs of big things to come: drawings for Leroy, the Mexican Jumping Bean—a short story written by his fellow Carnegie Tech classmate Philip Pearlstein—marking Warhol’s first work to accompany a narrative; and a homework assignment depicting the novel All the King’s Men as an illustration. Both are included in the exhibition.

That early professional chapter in the life of Andy Warhol took the artist to New York City. Soon, he was making a name for himself and a better than decent living as major publishing houses such as Doubleday, Harper & Brothers, and J.B. Lippincott commissioned him to design their dust jackets.

His cover renderings for Pistols for Two and The Saint in Europe—both part of the popular Crime Club series of the day— and his illustrations for Amy Vanderbilt’s Complete Book of Etiquette show a willingness to revise and rework his submissions in order to meet his clients’ needs. According to Price, these early examples aren’t readily identifiable, at least to most people, as Warhol’s. His signature style was still evolving.

Before he went Pop, Warhol focused a great deal of his creative energy on self-publishing. It was through books that the artist worked out many of the themes that would define his career: documentation, reproducibility, mass-produced visual culture, and authorship. In addition to his famous coloring parties, he enlisted his mother, Julia, who moved to New York City in 1952 and lived with her son for the next 20 years, to brand his projects with her fancy script.

Warhol was nothing if not a pragmatist. “There was a practical side to these collaborations,” Price says. “He simply needed more hands; it was a means to a goal.”

The book boss

If the goal was just to publish, Warhol far surpassed expectations by producing an extraordinarily large number and diverse assortment of products. There were books based on his personal interests (In the Bottom of My Garden, À la Recherche du Shoe Perdu), those he sent as gifts or promotional pieces (Love Is a Pink Cake, A Is an Alphabet), children’s books (The House That Went to Town, There Was Snow on the Street and Rain in the Sky), books about animals (25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy, Velvet the Poodle), and satire (Wild Raspberries).

The one constant was Warhol’s ever-expanding construct of what a book was and what it was meant to do. “He made books that didn’t have any images and books that didn’t have any text,” Price says. “It really depends on which book you’re talking about, whether the form is the art or the content is the art.”

As the somewhat sheltered ’50s gave way to the seemingly boundless ’60s, Warhol’s notoriety, both as an artist (enter the Campbell’s Soup Can) and as a celebrity (The Factory doors swung open) was rapidly gaining traction. Embarking on new collaborations with musicians, poets, and filmmakers, it’s no wonder his books also followed such divergent paths.

He established one of those partnerships with his assistant, poet Gerard Malanga. Together they produced Screen Tests / A Diary, a collection of black-and-white stills culled from Warhol’s famous short, silent films of famous visitors to The Factory. The filmstrip photos of the likes of Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, and Edie Sedgwick are juxtaposed with poems written by Malanga specifically to accompany each portrait.

The two would later publish Chic Death, again joining Warhol’s visuals—his Death and Disaster paintings—with Malanga’s words.

Words, in the form of a transcript of the amphetamine-fueled, Factory-discovered actor Ondine talking for 24 hours, dominate Warhol’s 1968 book, a, A Novel, hailed by one critic as a “new kind of Pop artifact.” The opposite can be said about the scale model of the Marilyn Monroe Book, uncovered in Time Capsule 55. Never actually printed, this handmade prototype is comprised of 38 octagon-shaped pages that accordion out to reveal abstract details taken from Warhol’s famous Marilyn silkscreen prints. When fully opened, this concertina-like book reaches nearly 30 feet in length.

Andy Warhol’s Index (Book) is truly a mixed bag of genius and a precursor to the multimedia platforms of today. The first of several books to defy the definition of a book, this seminal publication has been called a “children’s book for hipsters.” The cover image of Warhol and company assembled in front of his Brillo boxes is a negative printed in silver and black. The inside is bursting with pop-ups, including a Hunt’s tomato paste can and an elaborate castle; objects made to be removed , a balloon and a noisemaker; audio by way of a flexi-disc featuring a four-minute interview with the Velvet Underground’s Nico and others; and an advertisement for the book itself promoting of all things: a “do-it-yourself nose job.”

Warhol’s last two decades proved to be less prolific, at least in terms of books. Mined from his tape-recorded musings, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) offers the artist’s take on just about everything. While Warhol is listed as the author, his assistant at the time, Pat Hackett, was the unacknowledged ghostwriter. Hackett was, however, credited for her role in helping to craft their next venture—POPism: The Warhol Sixties, a meditation on the beginnings of the movement.

Several of Warhol’s final projects seemed to carry him full circle, taking him back to his days as an illustrator: children’s books featuring offset reproductions of his Toy paintings and the Vanishing Animals series, a collaboration with environmentalist Kurt Benirschke.

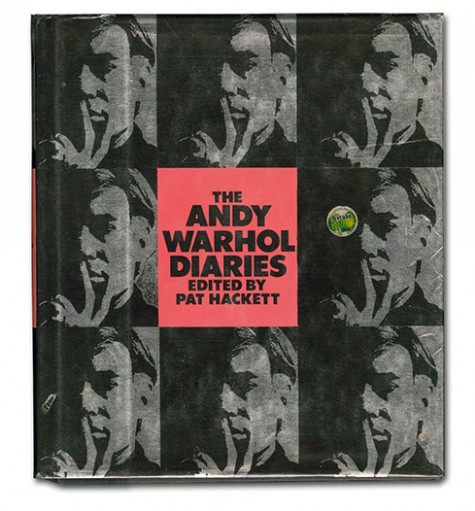

Of course, in the aftermath of Warhol’s death in 1987, plenty of books have been written about him: there’s Hackett’s edit of The Andy Warhol Diaries, Victor Bockris’ Warhol: The Biography, and Wayne Koestenbaum’s Andy Warhol: A Biography not to mention any number of compilations of his work.

The old saying tells us never to judge a book by its cover, but is it fair to judge a man by his books? “Warhol was all about accessibility and getting his work into the hands of the masses,” Price says.

“He is such a ubiquitous artist. There’s so much material from each decade, it has absolutely changed my perspective. I have a deeper understanding and respect for him.”

Warhol By the Book is supported in part by the Affirmation Arts Fund.