ExposuresTravis K. Schwab: Lost & Found

"Exposures 4: Travis K. Schwab: Lost and Found"

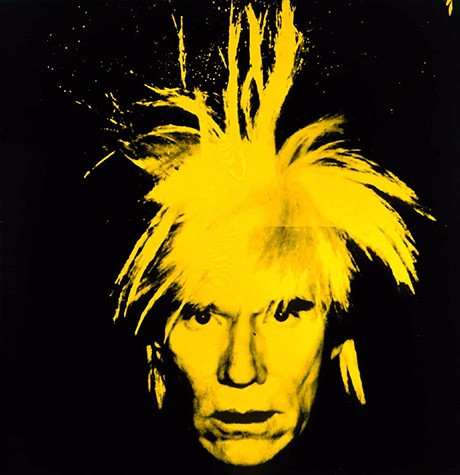

My first known encounter with Andy Warhol’s work was a spot on television when I was a little kid. It promoted different attractions in Pittsburgh, and it featured The Andy Warhol Museum by showing one of his pieces. It was the late-career work Self-Portrait (1986), of Warhol looking straight at the viewer with his famous wig sticking up in different directions, as if he were recently electrocuted. I remembered not understanding who or what it was supposed to be, but it was an image that stuck with me because it surprised me.

It wasn’t until I got older that I realized who Warhol was and what he did. Around my late teens, I discovered the experimental rock group The Velvet Underground, for which he produced the band’s first album along with designing the record cover. By that time, I thought of him more as a person in the music scene and did not really understand his large body of artwork. Later, when I was studying graphic design, I was more attentive to Warhol and started looking at his work through the lens of a young graphic design student. His use of color, composition, the selection of images, and the step/repeat method in his silkscreens were a huge influence on how and what I painted.

With this Exposures series, Lost & Found, I made oil on canvas paintings that focus on Warhol’s photography and film works to coincide with the large book selection of Warhol’s monographs and other published books featured in The Warhol Store. Also included are some paintings based on discarded photobooth strips from museum visitors. Assistant Curator Jessica Beck provided me with a collection of photobooth pictures to incorporate with the other paintings in the installation. These lost-and-found images of previous visitors remind me of a Warhol photograph or his Screen Tests, so they are somewhat of an indirect extension or continuation of his photographic work. The people in the photobooth pictures are “familiar” strangers that represent the general public brought to the museum via Warhol and his work. They are small snapshots of visitors past and present.

The three large gray paintings in the store windows, which show the back of Warhol’s head (it’s almost as if he’s looking into The Warhol Store), focus on the infamous wig. A sort of “anti-portrait” where you don’t see the whole sitter’s face but you recognize who it is. These “wig” paintings are based on photographs circa the early 1970s.

As I was working on the project, I noticed Warhol’s films themselves have a very painterly look to them. For instance, one of my paintings is based off of his very first film Sleep (1963), where there is some movement and camera angles, but for more than five hours you see a man being essentially still, almost posing for a painting. He did similar films like this where there isn’t much action, but there doesn’t need to be. A lot of my own paintings are based on photos I snapped of movies, TV, and even YouTube clips, so approaching Exposures this way was nothing new, but it gave me a much better appreciation and unique perspective of Warhol’s film work.

Thanks to The Warhol and its staff, and a big thanks to Jessica Beck for her wonderful input and very generous support with this project. Exposures: Travis K. Schwab: Lost & Found is on view in the museum’s street-facing windows in The Warhol Store through November 22, 2015.

Join us for an artist talk with Travis K. Schwab on Saturday, September 19, 2 p.m., in The Warhol Store. Guests are encouraged to engage in a community critique about his installation.