PittsburghMeeooaaww-AW-AWW

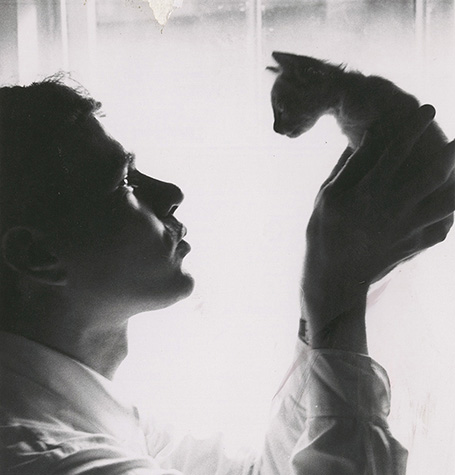

Edward Wallowitch, Andy Warhol with Kitten, ca. 1957, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © The Estate of Edward Wallowitch

The following is an excerpt from Matt Wrbican’s essay “Meeooaaww-AW-AWW” about Andy Warhol, Ai Weiwei, and cats that appears in the exhibition catalogue Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei. The catalogue was produced in conjunction with the exhibition Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei, on view at The Warhol June 4–August 28, 2016.

Even when domesticated, the cat embodies freedom. Cats generally do as they wish, not as instructed.[1] In attitude and behavior, they are the opposite of dogs, which are widely considered ‘man’s best friend’. Contrarily, a cat can be very close to a human, but almost always on its own terms; the English-language expression ‘like herding cats’ encapsulates the feline’s autonomy. Cats, while usually quiet, also possess a wider range of vocalizations – spitting, hissing, purring, chirping and more – than their canine counterparts. Their expressive use of these sounds (as many as 100, according to some sources) indicates their complex desires.

Many of the most celebrated modern Western artists were closely associated with cats, as can be seen in photographs of Jean Cocteau, Gustav Klimt, Frida Kahlo, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. At points in their lives, both Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei have lived with an abundance of cats. Warhol is alleged to have had as many as twenty-five cats in his home at once, while Ai’s studio (FAKE) harbors a reported forty felines.[2] The small furry animals are a frequent subject for both artists, including numerous postings to Ai’s social media feeds. Cats have appeared in art since the time of ancient Egypt; perhaps most frequently in the nineteenth-century Art Nouveau work of Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen. One of the most unusual works of art with a cat is by the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers, who recorded his Interview with a cat in 1970.[3]

Warhol and cats

In the 1950s, when Warhol was working as a commercial artist in New York, he was surrounded by a clowder of Siamese cats. Somehow reminiscent of the fossilized remains of dinosaurs, their paw prints were literally left on some of his artworks, including the cover of a copy of Wild Raspberries, the artist’s cookbook parody of 1959 made with his friend Suzie Frankfurt.[4] Having scampered about upon Warhol’s art, these furry creatures left their mark much more profoundly on the artist himself.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the Siamese first entered Warhol’s life, but he made reference to live-in felines as early as 1951 or 1952. A postcard Warhol addressed to Truman Capote, but failed to mail, is signed “from me and my cat.” Cards sent to and from his friend Tommy Jackson reference cats and “pussies.”[5] Old bios for Warhol published in the magazine Interiors track the expansion of his cat colony: eight in 1953, and ten in 1954.[6] With one exception, all of Warhol’s Siamese cats were named Sam, foreshadowing his reliance on repetition in his later Pop work. One wonders if Warhol was actually thinking of his cats when he created the Cow wallpaper, 1966, or Ethel Scull thirty-six times, 1963 (Metropolitan Museum of Art and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). The uniquely named Hester seems to have been the matriarch of Warhol’s brood.

The Siamese breed was peaking in popularity in the United States at the time, so it seems that he kept them in order to start breeding business on the side. Siamese cats are distinctively beautiful; they also are considered among the most intelligent and vocal of cat breeds. Even Hollywood (a frequent bellwether for Warhol’s creative efforts) jumped on the bandwagon: in the 1958 film Bell, Book and Candle, Kim Novak’s character (the beguiling modern witch Gillian Holroyd) was given a ‘familiar’ in the form of a Siamese cat named Pyewacket.[7] This considered, Warhol’s cat breeding business should have boomed, but his model failed. According to his friends, the cats became inbred and were notorious for bad behavior, crushing the plan for extra income. Warhol’s home was so overrun with cats that he had to give them away. The animals themselves, however, gained identities in the process: painter Philip Pearlstein and his wife Dorothy Cantor renamed their pair Cimabue and Sassetta, while author Ralph T. Ward (himself known as Corky) had Sweetie.[8]

…

Weiwei and cats

It seems no accident that Ai Weiwei, an internationally renowned artist now stripped of his Chinese passport, surrounds himself with twenty to thirty cats, many of them former strays to whom he’s given a very comfortable home in his studio.[26] Speaking about them, Ai says, “I love them and the people in this office all love these cats.” Just like Warhol’s Hester, most of Ai’s cats are not neutered. He says, “I didn’t choose them, they chose me.”

The cat’s essential characteristic of individual freedom is magnified in comparison to the restrictions placed on Ai, and the larger issues to which he draws our attention: absences of freedom, justice and responsibility. “They’re very independent. They [broke] several of my artworks. It’s [sic] very costly, these cats, but we cannot function [without them].”[27]

The cats and dogs in my home enjoy a high status; they seem more like the lords of the manor than I do. The poses they strike in the courtyard often inspire more joy in me than the house itself. Their self-important positions seem to be saying, ‘This is my territory,’ and that makes me happy. However, I’ve never designed a special space for them. I can’t think like an animal, which is part of the reason why I respect them; it’s impossible for me to enter into their realm. All I can do is open the entire home to them, observe, and at last discover that they actually like it here or there. They’re impossible to predict.[28]

While perhaps only a coincidence, the cat is absent from figures of the Chinese zodiac depicted in Ai’s Circle of animals / Zodiac Head: Gold, 2010. There are several versions of the ancient origins of this zodiac. According to one, the animals were summoned by the Jade Emperor to a meeting, stating he would name each year according to the order in which the animals arrived; in another, Cat drowns after making a pact with Rat, which is the reason cats chase rats, in eternal revenge. There are many other cat myths in China, unrelated to the zodiac. One states that soon after the gods created the Earth, the goddess Li Shou, herself a cat, was made its overseer, and she and all of her fellow cats were given the ability to speak. Soon it became clear Li Shou was not up to the task, as she kept falling asleep. The gods asked Li Shou to choose her successor, and she picked humans, who were then given the power of speech at the expense of cats.[29]

In the documentary film Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, the many cats of FAKE are seen lounging and patrolling the studio. In a widely known scene, one cat (Tian Tian) is captured demonstrating his unusual ability to open a door. The artist asks:

Where did this intelligence come from? All the other cats watch us open the door. So I was thinking, if I never met this cat that can open doors, I wouldn’t know cats could open doors. Cats can open the door, but only men can close it.[30]

Ai’s observation can be read as a critique of humans’ misuse of power. Perhaps it is time for us to hand back the reins of power – and the power of speech – to Li Shou? Ai claims that each time he gives an interview at his studio, one particular cat, Lai lai, is always present: ‘He’s never missed a word’.[31] Does this cat possess a vestigial understanding of the long-lost ability to speak?

…

The full essay is printed in the catalogue Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei, available for purchase in The Warhol Store. The catalogue is published by NGV, in collaboration with The Warhol and Ai, and edited by Eric Shiner, The Warhol’s director, and Max Delany, former NGV senior curator, contemporary art. Alongside reproduced images by both artists are essays by an international team of art experts, curators, and scholars that survey the scope of the artists’ careers and interpret the impact of Warhol and Ai on contemporary art and life.

Notes

[1] In the author’s many years of experience with numerous domestic cats, he has been able to train only two (Batgirl and Batman, tuxedos born to a tortoiseshell mother) to recognize his whistle.

[2] Ai’s assistant Darryl Leung informed the author that the number of resident cats at FAKE fluctuates between twenty and thirty.

[3] Recorded at Broodthaers’s Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles), 12 Burgplatz, Düsseldorf, 1970. Broodthaers interviewed a cat regarding esoteric subjects, such as market trends in contemporary art. The work contains a transcription of the interview. An edition of fifty copies was published by Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, in 1995.

[4] This copy is in Warhol’s Time Capsule 12, held by The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. Wild Raspberries is a brilliant parody of French cuisine, which was becoming enormously popular in the United States at that time.

[5] This correspondence is found in Warhol’s archives, in the collection of The Andy Warhol Museum.

[6] These references were initially noted by Neil Printz; my reference is Lucy Mulroney’s ‘One blue pussy’, Criticism, vol. 56, no. 3, Summer 2014, pp. 559–92. Mulroney cites Printz’s work.

[7] The name Pyewacket has roots in the horrific Salem witch trials in early American colonial history of the mid-seventeenth century.

[8] Named after the painters of the early Italian Renaissance Cimabue (Bencivieni di Pepo, Florence c. 1240–1302) and Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni, c. 1390–1450).

[26] In an email to the author on 7 May 2015, Ai’s assistant Darryl Leung wrote: “The cats all come to the studio in different ways. Sometimes they are found on the street; sometimes they jump into the studio by their own volition, other times friends might bring the cat to the studio.”

[27] Ai Weiwei in 258 Cats, Hosen Tandijono, China, 5:38 mins, 2013, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rFUVigZYyJo>.

[28] Ai Weiwei, ‘Here and now’, posted 10 May 2006, in Ai Weiwei’s Blog: Writings, Interviews and Digital Rants, 2006–2009, ed. & trans. Lee Ambrozy, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA & London, 2011, p. 49.

[29] A folk tale from Quebec concerns a specific ‘talking cat’ named Chouchou; it was first published in 1952.

[30] Ai Weiwei in Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, Alison Klayman, Expressions United Media, MUSE Film and Television, Germany, 90 mins, 2012.

[31] Ai in 258 Cats.